LONDON: In the days of imperial heavy-handedness, when Britain ruled the waves and waived the rules whenever it suited its interests, London’s favored technique for dealing with those who dared challenge its global hegemony was to “send a gunboat.”

In the 21st century, for the militarily impotent, postcolonial state still clinging to delusions of imperial grandeur that Britain has become, sanctions are the new gunboat.

In Iraq and Afghanistan, where the enemy was perceived to be weak, Britain was still prepared to deploy actual force. Faced with a far-from-weak Russia, however, Britain, the US and a NATO revealed by the Ukraine crisis to be unexpectedly timorous have sheathed their swords and wielded sanctions instead.

Deciding which individual or regime should be punished is obviously an elastic consideration, guided by a cynical risk-benefit calculation. Can we do this without any blowback?

Take the case of China. It would not be hard for the UK government to argue that, 25 years after Britain transferred sovereignty over Hong Kong to the People’s Republic, Beijing has reneged on some of the commitments it made over democracy, human rights and governance.

Not hard, but not realistic.

Shaking a stick at the Russian bear is one thing, but realpolitik dictates that rattling the cage of the world’s workshop is unthinkable — a cynical calculation that renders the whole sanctimonious exercise of sanctioning morally dubious.

As more Russian businessmen and women, as well as their enterprises, find their way onto Britain’s blacklist, the rapidly escalating program of sanctions feels less like a carefully considered, surgically precise intervention and more like a witch-hunt.

UK prime minister Boris Johnson has said Russian oligarchs in London will have nowhere to hide. (AFP)

The extraordinary scale of the sanctions frenzy can be witnessed at Russian Asset Tracker, a website being run by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project, a consortium of investigative centers, media and journalists.

The list of names and associated assets worth billions of dollars — including massive houses, helicopters, aircraft and, of course, fleets of superyachts — is impressive. The implication, of course, is that all these things are ill-gotten gains. What the OCCRP lacks, however, is any evidence to that effect, which leaves the whole exercise feeling like sour grapes.

In short, a pitchfork-wielding mob is baying for Russian blood, and a UK government with populism woven into its DNA is obliging.

Ironically, given that association with Moscow is once again the crime du jour, the whiff of McCarthyism is in the air. MPs in the House of Commons have even been clamoring to have the legal firms that represent the interests of the blacklisted Russians “named and shamed.”

So much for Britain’s famed judicial integrity. Even someone accused of child murder is entitled to a lawyer, without that lawyer facing social ostracism.

It has been argued that the Russian “oligarchs” and “kleptocrats” who have bought homes and properties and made lives in the UK have done so because Britain’s regulatory environment is weak and easily exploited by individuals seeking to launder money.

In fact, the UK has one of the toughest financial governance regimes in the world. The Russians and the wealthy of many nations choose Britain as their European base precisely because the legal, financial and judicial environment is reassuringly stable, accessible and dependably objective.

Until now, that is. The smash-and-grab raids that are hitting anyone who can be even vaguely linked to the Russian government are doing nothing for Britain’s reputation as a country of law and order, and commercial and judicial probity.

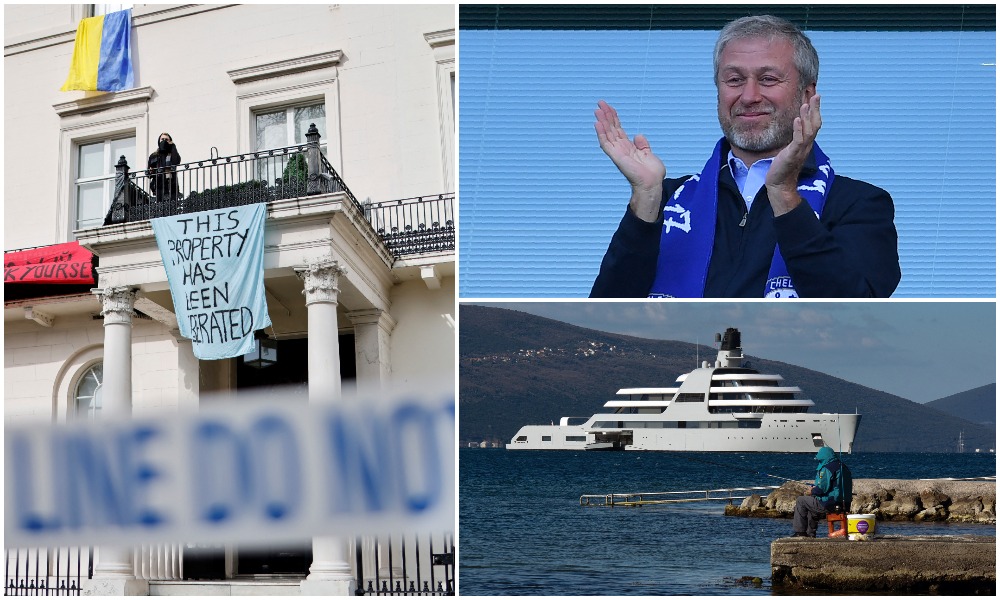

Chelsea owner Roman Abramovich (L) is the most high profile Russian oligarch to be sanctioned by the UK; also pictured are Russian businessman, co-founder of Alfa-Group Mikhail Fridman (top) and Russian tycoon Oleg Deripaska. (AFP)

It is, perhaps, a measure of the shaken confidence in British justice that no challenges against any of the sanctions have yet been lodged with the High Court, which is qualified to hear them under the Human Rights Act 1998. Once that process is exhausted, a plaintiff has recourse to the European Court of Human Rights.

Much of Britain’s service-based economy, especially in the City, is dependent on the wealthy foreigners who choose to operate there. Watching what is now happening to the Russians, many will be wondering if they, and their assets, are safe, or whether the regulatory rug could be pulled from under them at a moment’s notice should their own country of birth offend Britain in some way.

The imposition of sanctions, and the overnight pillorying of individuals who, until Russia invaded Ukraine, were treated as pillars of British society, flies in the face of the universal legal dictum that one remains innocent until proven guilty.

Setting aside the question of what amounts to “guilt” in these circumstances — and it is unclear what qualifies Britain to decide what constitutes commercial criminality in another country — no arrests have been made, no charges brought, no trials conducted and no juries assembled to pass judgments.

There has, in other words, been no adherence to the legal process of which Britain professes to be proud, and to which all who live and do business in the UK look for assurance and impartiality.

And where is the British government getting the seemingly comprehensive information and potentially libelous accusations about individuals that it is happily publishing? Could it be that it has had this information all along, in which case why did it not act on it before? Or perhaps it is being fed intelligence by sources whose interests lie in sabotaging the affairs of the accused, for either personal or commercial motives?

At best, sanctions are an imprecise instrument, a legislative cluster bomb deployed indiscriminately, in this instance seemingly in the vague hope of somehow influencing Russian leader Vladimir Putin because someone to whom his government once gave a contract might beg the president to change course so he can get his superyacht out of the pound.

For the imposers of sanctions, rather like the pilots of B-52 Stratofortress bombers dropping their indiscriminate payloads on unseen targets from a great height, freezing funds is an exercise in remote warfare, requiring no one to get their hands dirty, other than from the ink on a smudged signature.

The UK government said on March 3, 2022, it was imposing sanctions on billionaire businessman Alisher Usmanov (pictured right, with Vladimir Putin) as part of punitive measures over Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine. (AFP)

The UK’s Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Act 2018 is a lengthy document, laying out each and every situation in which the British government can impose sanctions.

In fact, as anyone who has read all 3,000 words of the act will know, the army of lawyers that doubtless toiled over the crafting of its 71 pages could have saved a few trees and a lot of time by boiling down the whole thing to a single, frank sentence: “The British government can impose sanctions on any individual or organization it sees fit, anywhere in the world, and for whatever reason and purpose it deems appropriate.”

The act is an extraordinarily high-handed document. It grants any “appropriate minister” the power to make sanctions under three circumstances: To comply with a UN obligation; to comply with “any other international obligation” (itself a curiously vague term); or — and here’s the wild card — “for a purpose within subsection 2.”

The purpose of such an act is to provide the government with the legal justification for its actions, but of course this is a charade. In imposing sanctions under its terms, the government is not following the edict of some universal third party, such as the UN, but is playing by rules that it has created itself.

There are nine “purposes” listed in section 2, several of which are vague to the point of being meaningless. Depending on the self-interest or inclination of any party in power, “in the interests of national security,” to “further a foreign policy objective of the government,” or to “provide for or be a deterrent to gross violations of human rights,” could arguably be applied to almost any situation in any country anywhere in the world at any time.

Of the nine, however, it is perhaps the last on the list that raises eyebrows the highest. The government, it states, may impose sanctions to “promote respect for democracy, the rule of law and good governance.”

Set aside for the moment the impertinence of the UK seeking, despite its diminished status in a post-imperial world, to impose its brand of “democracy” on anyone — because, after all, look how well that has worked out in Iraq, Afghanistan and, yes, even Iran, all countries in which the UK has meddled in the interest of imposing “respect for democracy.”

And “the rule of law?” Whose law?

Placards in support of Ukraine are seen on a building opposite the Russian Embassy in London, on March 18, 2022. (AFP)

As for “good governance,” this would be hilarious if it were not so breathtakingly hypocritical.

“Good governance” did not appear to be much on the minds of the Conservative government when its MPs and leadership happily accepted funding from the very people it has now decided are bad eggs, or casually endorsed the very financial governance system that allowed them to purchase property in London on an industrial scale, apparently — as they now claim — with no questions asked about where their money came from.

Time, perhaps, for the UK government to sanction itself?

The Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Act is the type of instrument which, had it been created by a foreign power that happened to find itself in Britain’s bad books, would have exposed its authors to sanctions for its clear disregard for, well, “respect for democracy, the rule of law and good governance.”

Of course, the enthusiasm for sanctions predates the act. Some of the current sanctions in force in the UK, imposed by the EU when Britain was still a member state, date back up to 20 years, affecting individuals, organizations and governments of a dozen or more countries, ranging from Belarus and Burundi to Lebanon and the People’s Republic of Korea.

And it is the longevity of many of these sanctions that reveals a stark truth — they do not work, except, of course, as an exercise in gesture politics, designed largely for domestic consumption.

Remember EU Council Regulation number 833 in 2014, triggered after Russia annexed the Crimean peninsula and designed to “encourage Russia to cease actions destabilizing Ukraine or undermining or threatening the territorial integrity, sovereignty or independence of Ukraine”?

No? Well, who does? Certainly not Putin. Having entirely failed in any of its objectives, that much-lauded and wholly ineffective intervention was quietly revoked in 2019.

Spanish authorities impounded a yacht suspected of belonging to a Russian oligarch as part of European Union sanctions over the Ukraine war, the transport ministry said. (AFP)

Whatever the rights and wrongs of Russia’s latest invasion of Ukraine, grabbing cash and assets from so-called “oligarchs” and “kleptocrats” with whom the British government was, until the recent turn in the tide of political convenience, the best of pals, is a blunt instrument of dubious legality and proven ineffectiveness.

The words of British Foreign Secretary Liz Truss — “oligarchs and kleptocrats have no place in our economy or society. The blood of the Ukrainian people is on their hands; they should hang their heads in shame” — is hypocritical sanctimony of the worst kind.

The UK government did not discover only last week that Roman Abramovich owned Chelsea Football Club, a penthouse overlooking the club’s ground and a mansion close to Kensington Palace. Yet only now, years after Abramovich invested GBP140 million in the club in 2003, is the government choosing to categorize him as a “pro-Kremlin oligarch” who has “received preferential treatment and concessions from Putin and the government of Russia.”

All over the world, including in Britain — where incidentally, the scandal of multimillion-pound pandemic contracts being handed to the wholly unqualified friends of ministers appears to have evaporated — companies are paid by governments to carry out projects. Are their owners all to consider themselves one geopolitical shift away from an accusation of criminality?

It has not gone unnoticed that Abramovich, who has the highest profile of all the Russians in the UK, was not designated a target in the first round of sanctions, but only after a political hue and cry.

And what of those British MPs who have been funded by Russians who now find themselves on the Treasury’s blacklist for their links to Putin? Shouldn’t they, too, be sanctioned for their links, albeit once-removed, to the Russian president?

The true, lasting impact of the sanctions regimes imposed by Britain, the EU and the US will, as usual, be felt by unintended targets.

At best, some extremely wealthy individuals — most of whom, curiously, were given sufficient early warning in the UK to allow them to protect their funds, if not their properties — will be temporarily inconvenienced.

A pro-Ukrainian demonstrator holds a placard opposite the Russian Embassy in London, on March 18, 2022. (AFP)

Reuters reported recently that at least five superyachts owned by Russian billionaires had been spotted anchored off the Maldives — nice at this time of year but, more importantly, lacking the required extradition treaties to allow sanctioned seizures of assets to be enacted.

Sanctions bite hardest for ordinary, hard-working people, who are unable to weigh anchor and cruise away to calmer waters — in this case citizens of Russia and Belarus facing catastrophic disruption to their lives through no fault of their own.

The list of companies that have pulled out of Russia, including Coca-Cola, McDonald’s and Starbucks, is long, but not as long as the list of anonymous employees who will have lost their jobs.

The other victims may be a small group of not-so-ordinary people, or, rather, the companies they represent and which now find themselves trapped — again, through no fault of their own — in a financial no-man’s land between the lines drawn up between the West and Russia.

Until Russian forces invaded Ukraine, it was perfectly legal — indeed, enthusiastically encouraged by trade-hungry countries such as the UK and the US — to deal with Russia.

Saudi Arabia, like many other nations, has extensive commercial and diplomatic relations with Russia (which arguably date back to 1932, when the Soviet Union became the first country to recognize the newly founded Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.)

As two of the world’s major exporters of fossil fuels, they have cooperated, as indeed they must, on regulating the production and pricing of oil.

Oil aside, in 2019 Russian exports to Saudi Arabia, ranging from cereals and seed oils to copper, iron and steel, were worth over $1.25 billion, with the Kingdom in turn exporting goods to Russia worth $229 million, including a healthy trade in amino-resins, a key component of plastics.

A banner in the colours of Russia’s national flag, and depicting an image of Chelsea’s Russian owner Roman Abramovich, is pictured in the stands during an English Premier League match between Chelsea and Newcastle United. (AFP)

In January, before the latest Ukraine crisis erupted, at a cultural forum at Expo 2022 in Dubai, the chair of the Federation of Saudi Chambers spoke enthusiastically of the potential for wider cooperation between the Kingdom and Russia in all commercial fields, from banking to import-export.

Could all this be at risk?

It is not yet clear if the sanctions net cast by Britain, the US and the EU will be thrown wider to fall upon other entities, beyond “oligarchs and kleptocrats,” that have had dealings with Russia.

Logically, third-party countries such as Saudi Arabia and their commercial endeavors should have nothing to fear. As both Saudi Arabia and the UAE have indicated with their disinclination to fall in line behind Western calls for raised oil production to stem prices driven upwards by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, this is not their war.

But the legislation underpinning the UK’s sanctions regime is so broad in reach, and the pitchfork-wielding mob of public opinion so sanctions-happy, that in theory there is no limit to the types of situation in which this blunt sword could be wielded.

Directly or indirectly, there could be consequences for Saudi Arabia, according to Jonathan Compton, partner and group head of dispute resolution at London City law firm DMH Stallard.

“This is a difficult one,” he said. “The UK sanctions apply only to Russia and Belarus. Inevitably, though, trade and financial flows will be monitored and, I suspect, pressure brought to bear.

“The removal of Russia from the Swift system will have a negative effect on trade with third countries such as the Kingdom — indeed, the sanctions are designed for this purpose.”

As the witch-hunt rumbles on, few are the voices raised in objection to the anti-Russian sanctions — indeed, social media is alive with Russophobic denunciations of all kinds, while in the US, bars across the country have made a great show of pouring bottles of Stolichnaya vodka down the drain, apparently unaware that it is produced in Latvia, not Russia.

There is no doubt that the events unfolding in Ukraine are distressing, and that the prospect of a war in Europe in the 21st century is unthinkable. But lashing out at bit players, albeit extremely wealthy ones, who are vaguely associated with the Russian regime, is an unwarranted act of displacement.

NATO and its member states have demonstrated clearly that they are afraid to face down an aggressive Russia. Choosing instead to pick off individuals with a questionably legal bombardment of sanctions, sabotaging economies across the world in the process, is a poor substitute for courageous and intelligent diplomacy.