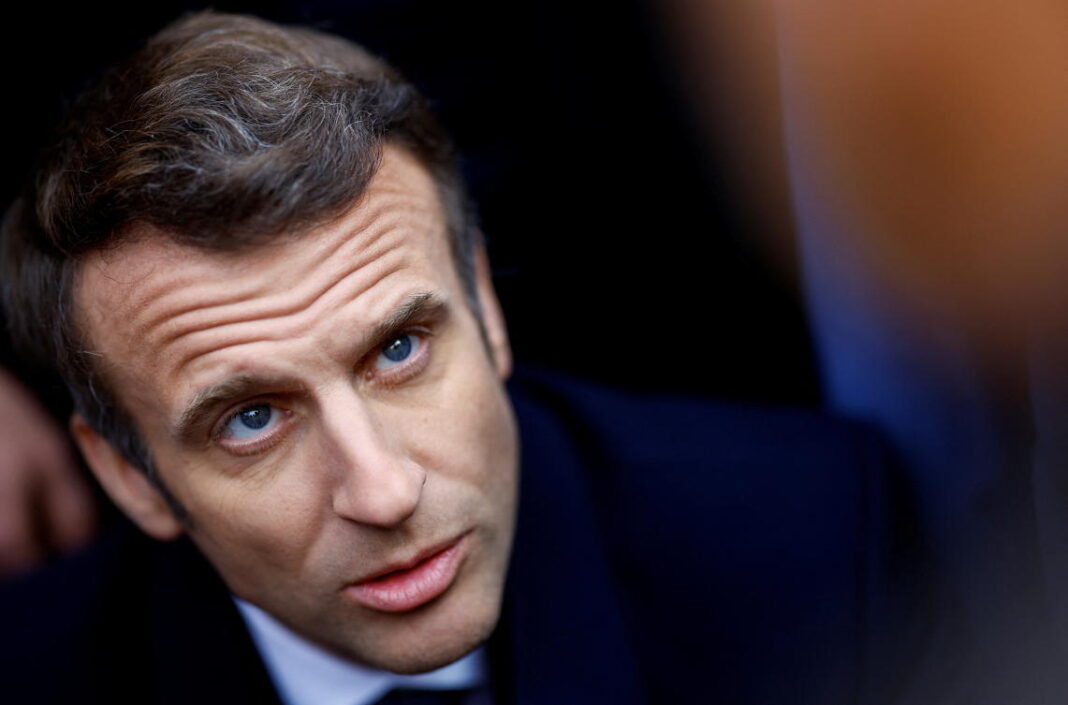

PARIS: As French President Emmanuel Macron prepares to hold his first big rally Saturday in his race for re-election, his campaign has hit a roadbump.

It’s been dubbed “the McKinsey Affair,” named after an American consulting company hired to advise the French government on its COVID-19 vaccination campaign and other policy. A new French Senate report questions the government’s use of private consultants, and accuses McKinsey of tax dodging. The issue is mobilizing Macron’s rivals and dogging him at campaign stops ahead of the April 10 first-round vote.

His supporters hope he can rev up his campaign and drown out his detractors at Saturday’s rally in a huge arena west of Paris. Macron, a centrist who has been in the forefront of diplomatic efforts to end the war in Ukraine, has a comfortable lead in polls so far over far-right leader Marine Le Pen and other challengers.

But the word “McKinsey” is becoming a rallying cry for those trying to unseat him. Critics describe the government’s 1 billion euros in spending on consulting firms like McKinsey last year as a sort of privatization and Americanization of French politics, and are demanding more transparency.

The French Senate, where opposition conservatives hold a majority, published a report last month investigating the government’s use of private consulting firms. The report found that state spending on such contracts has doubled in the past three years despite mixed results, and warned they could pose conflicts of interest. Dozens of private companies are involved in the consulting activities, including giants like Ireland-based multinational Accenture and French group Capgemini.

Most damningly, the report says McKinsey hasn’t paid corporate profit taxes in France since at least 2011, but instead used a system of “tax optimization” through its Delaware-based parent company.

McKinsey issued a statement saying it “respects French tax rules that apply to it” and defending its work in France, but didn’t elaborate.

McKinsey notably advised the French government on its COVID vaccination campaign, which got off to a halting start but eventually became among the world’s most comprehensive. Outside consultants have also advised Macron’s government on housing reform, asylum policy and other measures.

The Senate report found that such firms earn smaller revenues in France than in Britain or Germany, and noted that spending on outside consultants was higher under conservative former President Nicolas Sarkozy than under Macron.

Budget Minister Olivier Dussopt said the state money spent on McKinsey was about 0.3 percent of what the government spent on public servants’ salaries last year, and that McKinsey earned only a tiny fraction of it. He accused campaign rivals of inflating the affair to boost their own ratings.

“We have nothing to hide,” said Amelie Montchalin, the government’s minister for public service.

The affair is hurting Macron nonetheless.

A former investment banker once accused of being “president of the rich,” Macron saw his ratings resurge when his government spent massively to protect workers and businesses early in the pandemic, vowing to do “whatever it takes” to cushion the blow. But his rivals say the McKinsey affair rekindles concerns that Macron and his government are beholden to private interests and out of touch with the concerns of ordinary voters.

Everywhere Macron goes now, he’s asked about it.

“The campaign should be about purchasing power, how to settle security problems, how to end the war (in Ukraine),” he told voters Thursday. “Don’t make it about a false issue.”

On a talk show last Sunday, he said defensively, “If there is proof of manipulation, let them take it to court.”

A woman who lost her father to COVID-19 filed a lawsuit Friday accusing McKinsey and other consulting companies of misusing public money when they were hired to advise the government on mask and vaccine supplies. Julie Grasset now runs a support group for people who lost loved ones in the pandemic.

“It’s a serious issue. We are talking about public health,” Grasset said.

The financial prosecutor’s office did not comment. It could take weeks for prosecutors to decide whether to take up the case, one of several Grasset and others have filed involving the government’s handling of the pandemic.

Emmanuel Macron’s re-election push troubled by ‘McKinsey Affair’