LONDON: From a military perspective, the French invasion of Egypt in 1798, an attempt to disrupt British trade and influence in North Africa and India, was a complete failure. For the world’s understanding of 3,000 years of ancient Egyptian history, however, it would prove to be an accidental triumph.

An army of 50,000 men under the command of Napoleon Bonaparte landed at Alexandria on July 2, 1798, and over the next three years there were a series of victories, and the occasional defeat, for the French troops in Egypt and Syria.

But after the British navy sank Napoleon’s fleet in Aboukir Bay at the Battle of the Nile on July 25, 1799, the dwindling, disease-ravaged French army, harried by Ottoman and British forces, found itself trapped in a hostile, alien land. With no way out, and no chance of reinforcement, the end was inevitable.

Napoleon knew this, and on the night of Aug. 22, 1799, he abandoned his troops and slipped back to Paris and his ultimate destiny — in 1804, he would be crowned emperor of France.

The remains of his army in Egypt clung on, even after Napoleon’s successor as commander was assassinated, until it finally surrendered to the British at Alexandria on Sept. 2, 1801.

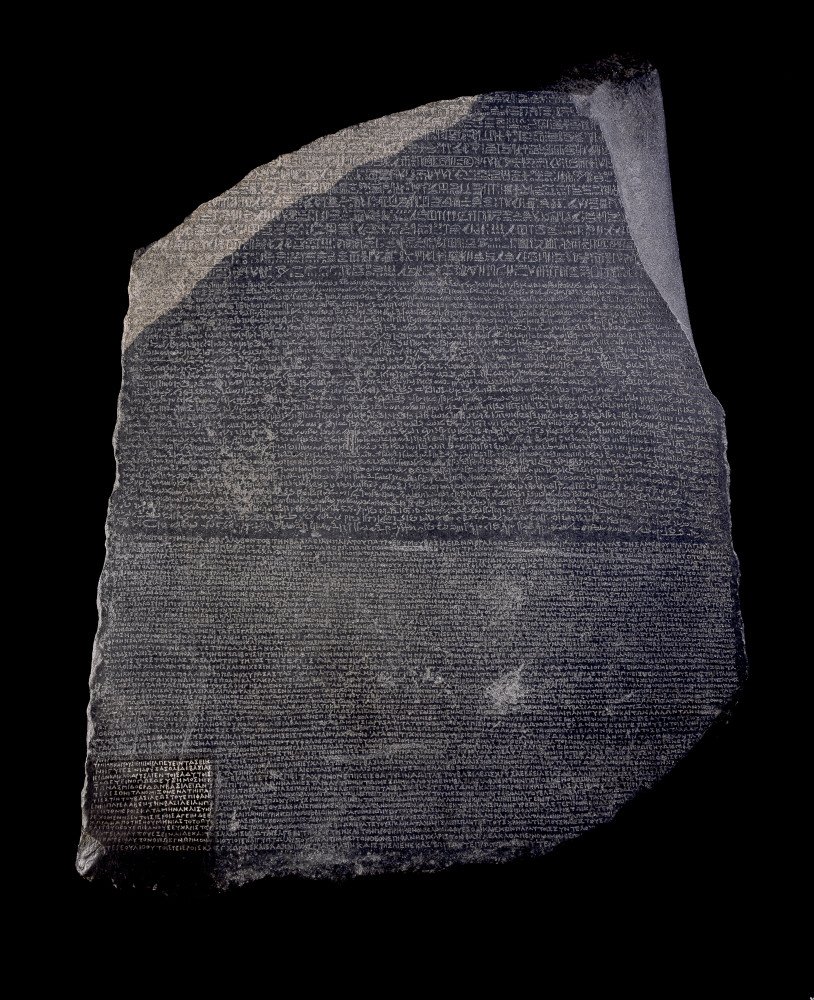

As part of the expedition, Napoleon had ordered the wholesale looting of antiquities to be taken back to France. But, after the French surrender, most of these fell into the hands of the British. Among the spoils shipped back to the British Museum was a block of polished stone engraved with writing in three different languages — ancient Greek, Demotic, and Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Discovered in July 1799 by a French army engineer who had been strengthening the defenses of a captured 15th-century Ottoman fort near Rosetta on the west bank of the Nile, the object became known as the Rosetta Stone.

It would prove to be the key to understanding ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Although many European scholars were fluent in ancient Greek, it would be more than two decades before they were able to crack the Rosetta code. When they did, it was a landmark moment in Egyptology, which the British Museum is celebrating this month with a major new exhibition that brings together a collection of more than 240 objects, including the Rosetta Stone.

The exhibition, “Hieroglyphs: Unlocking Ancient Egypt,” coincides with the 200th anniversary of the final breakthrough by French philologist and orientalist Jean-Francois Champollion in 1822.

“Deciphering the hieroglyphs on the Rosetta Stone unlocked 3,000 years of Egyptian history,” Ilona Regulski, curator of Egyptian written culture at the British Museum, told Arab News.

“Until then, nobody knew how far back the ancient Egyptian civilization went, or how long it lasted. But after his breakthrough, Champollion was able to translate the names of kings and establish a royal chronology which went back much farther in time than anyone had previously realized.

“Very soon, there also came the understanding that this was a complex civilization that had relationships with its neighbors, sometimes peaceful, sometimes violent, and step by step we came to understand the society better.

“From the Greek historians, who reported some practices that they saw, we knew that the ancient Egyptians mummified their dead. But we didn’t really understand how these people lived and experienced their world.”

Cracking the Rosetta code was a complex business that tested the minds of European academics. Although the stone featured three translations of the same decree, they were not alike word for word.

“Champollion and others started by looking at the Greek text and identifying words that appeared often, for example, the word for temple, or the title basileus (a term for monarch),” said Regulski. “They looked at the demotic text to see if there was a cluster of signs that appeared more or less in the same place.”

It was a reasonable start, but a process frustrated by the fact, not initially appreciated, that neither ancient Egyptian nor demotic were alphabet-based scripts, and that any one word could be spelled in many different ways in the same document.

Eventually, a sign list, a kind of ancient Egyptian dictionary, was created, “but it was not enough to understand the entire text, or to use it to read other inscribed objects,” said Regulski.

It was Champollion who finally figured out that hieroglyphics was a hybrid system.

“There are alphabetic signs, but also single signs that represent two or three letters, or even entire words,” said Regulski. “And some are silent signs, what we call ‘determinatives’ in Egyptology. You don’t read them in any way, but they indicate the meaning of the preceding word, telling you whether it’s a verb or a noun.”

Basically, hieroglyphics “appears to be a very simple, symbol-based language, but it’s much more complicated than that, and much more complex than an alphabetic script, and that took a long time to figure out.”

The script on the Rosetta Stone turned out to be a decree written in 196 B.C. by priests at Memphis, recognizing the authority of the Ptolemaic pharaoh Ptolemy V. It would have been written originally on papyrus, with copies distributed around the kingdom so the text could be engraved on stone slabs, or “stelae,” for display in temples throughout Egypt.

Over the following decades, nine other partial copies of the decree would be discovered at sites across Egypt. But the Rosetta Stone is the most complete and, without it, for example “the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun,” excavated by the British archaeologist Howard Carter in 1922, “would have looked very different,” said Regulski.

“It would have been difficult for Carter to identify the king, which is quite crucial, and his place in the context of the chronology of the 18th dynasty. We would just have a beautiful tomb with beautiful things.”

By the standards of ancient Egypt, the Rosetta Stone is not that ancient. “For us as Egyptologists,” said Regulski, “the stone, from about 200 B.C., comes very late in the story of hieroglyphics, a writing system that first came into use in about 3250 B.C.”

And in 200 B.C., hieroglyphics were already on the way out.

“The first really important change in Egypt was the use of Greek as the administrative language,” said Regulski.

“When Alexander the Great conquered Egypt in 332 B.C., people were already speaking Greek; the language was already circulating from the eighth century onwards, because of trade and because there were lots of Greek mercenaries who fought in the Egyptian army and settled in the country.

“But from Alexander the Great onward, and especially in the Ptolemaic periods, Greek became the language of administration and slowly pushed Egyptian out.”

Regardless of the historical context of the discovery of the Rosetta Stone, and its seizure by the British, “for the field of Egyptology, and for Egypt, it is definitely something to celebrate,” said Regulski.

“Today, there are many Egyptologists in the world, including our colleagues in Egypt, and we all work together, a huge community trying to refine our knowledge of ancient Egypt, which all came out of this one venture.”

Regulski, who spent two years working alongside Egyptian colleagues at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, could not be drawn on the vexed subject of whether the Rosetta Stone should be returned to its country of origin.

More than 100,000 artifacts from Egypt’s rich past will be housed in the Grand Egyptian Museum, currently nearing completion at a site west of Cairo, close to the Giza pyramids.

Among them will be the 5,400 treasures entombed with Tutankhamun more than 3,300 years ago, including his iconic death mask, which, after decades of touring the world, will finally come to rest where they belong.

However, the Rosetta Stone, the key to understanding it all, will remain in Britain.

The British general who accompanied the stone back to Britain in 1801 after it was taken from the French, chose to see it and 20 other pieces not as loot, but as “a proud trophy of the arms of Britain — not plundered from defenseless inhabitants, but honorably acquired by the fortune of war.”

The British Museum exhibition will feature the French capitulation document, on loan from the UK’s National Archives and displayed for the first time. This, said a spokesperson for the British Museum, is “the legal agreement which included the transfer of the Rosetta Stone to Britain … as a diplomatic gift … signed by all parties; representatives of the Egyptian, French and British governments.”

Today, an Egyptian government might justifiably take issue with the description of an officer of the Ottoman army as a rightful custodian of Egyptian heritage.

Certainly, at the time, no thought was given to whether the Rosetta Stone and other antiquities ought to remain in Egypt, a question that is becoming ever more acute today, in an era when pressure is mounting on Western institutions such as the British Museum to return the spoils of imperial wars and adventures.

“The only thing I would say is that having worked closely with Egyptian curators at the museum, it’s not a priority for many of them,” said Regulski. “I find it a bit sad that our relationship is framed in this way, about giving back objects or not, because our relationship with our Egyptian colleagues is about so much more than which individual objects went to this place, or that.

“It’s about celebrating ancient Egypt, and there is still so much to do in Egypt, so much to learn, to research and collaborate on, and that is the positive thing to focus on.”

The public fascination with ancient Egypt owes its origins to the discovery of the Rosetta Stone, the single most visited object in the British Museum, and “to a culture that left behind such a well-preserved, monumental testament to its existence that also has such a powerful visual appeal, which you don’t have in some other ancient cultures.

“I think the general visitor to a museum is drawn to this highly visual, artistic culture, including the writing system itself. If you compare it with cuneiform, for example, you’re going to be drawn more to hieroglyphics, because it’s so beautiful, so visually appealing. I think that’s what hooks people and encourages them to learn more about the culture.”

Certainly, the British Museum expects the exhibition, which will chart the journey to decipher hieroglyphs, from initial efforts by medieval Arab travelers and Renaissance scholars, through to Champollion’s triumph in 1822, to be one of its most popular to date.

‘Hieroglyphs: Unlocking Ancient Egypt,’ is at the British Museum from Oct. 13, 2022 to Feb. 19, 2023.